books

Whelm

Whelm is a unique and heady mix of the personal, the intellectual, and the wildly inventive. In a single poem, lonsinger can move from a study of ruin and rain to a prayer that she might have the “moxy of the torrential” and the power to let go to a discussion of our human problems with intimacy and the proclivity of the gods to intervene–connecting each idea to the next through the most surprisingly apt, intensely wrought language. Her poems are fascinated by the “in-betweenness” that occurs between the person observing and the object observed, between the lover and her beloved, even between different nesting objects that seem–only on the surface–easily to enclose each other. Whelm is full of shape-shifters that defy easy categorization: they focus on the possibilities and limitations of human connection through an examination of language, in all its alternating slippages and specificities, in all its wondrous beauty.

–Paisley Rekdal

dawn lonsinger’s work beautifully plies the seams between grandeur and banality, between identity and Fla-vor-ice, between the primal beauty of oceans, and (to steal her phrase) “the sadism of normalcy.” In the dark water of these poems, lonsinger gives voice to those things that cannot be categorized, enumerated, or named–love, language, music, the ghosts of the natural world–all the things that can save us.

–Anthony Doerr

I so admire the tension between the macro and micro worlds in dawn lonsinger’s Whelm. Whitmanesque inventories collide with intimate interiorities. dawn lonsinger turns a tough eye and a tender heart toward the experience of living fully in the rush of the Now and the flickering echoes of history. These are lushly rendered poems to savor and/or to devour.

–Nance Van Winckel

One of my favourite poems in Whelm is “Forage” which appears in first section. This poem combines much of what I admire in lonsinger’s poetry—her imagination, unusual linguistic play, and the ability of her images to subtly critique the confines, problems and crises of the contemporary world or what she calls the “sadism of normalcy.” [ . . . ] Love, however problematic and slippery, is what seems to be the poet’s answer to this flood that comes from both language and nature. . . . the repair of a world tenuously existing on the brink of social and ecological collapse.

– Review by Sandra Simonds in Southeast Review

A “collection” in the truest sense of the concept, Whelm is a cabinet of curiosities. In it we move through a poetic portal where her technical diligence and riveting alertness to the fractures of daily life give pleasure that overrides pain. More, lonsinger sutures these life’s fragments in a way that enables a more gentle understanding of how brokenness infuses that which provides joy. [ . . . ] In a world where we account for exponentially growing divisions and dissections, lonsinger uses a magic of the word to render this life affectively accessible to anyone who touches her page. [Her] poems narrate relationships global while local, invertebrate while mammal, terrestrial while liquid.

– Review by Hailey Haffey in Quarterly West

The book is a red hibiscus mouth. The book is a shadow box with another shadow box tucked into it. The book is waves and rain and rotting apples. The book is a transparent shirt over transparent skin over a transparent heart. The book is violence and regeneration. These poems disarm you by not giving you the metaphor(s) you expect. We find trees made of money, a river teeming with hippos, a town with fire alive in the mines beneath it, and a quiet, gentle elegy to a bus driver. To point to lonsinger’s language as lush, rich, or sumptuous in the landscapes of these poems, though not inaccurate, is to prettify/simplify the work of the language—to get to the edge of what is unsayable, that ravenous corner of the psyche that longs for connection. [. . .] lonsinger begins to walk/write the finest line—the one that exists on the edge of the abyss of the inexpressible, desirous self. It is when I encounter complicated, raw, finely honed, and (yes!) beautiful collections like Whelm, that I believe in the absolute relevance of writing about the body and how it desires and loves and hurts and withers and aches and pulses and sleeps.

– Review by Kate Rosenberg at Sugar House Review

In dawn lonsinger’s Whelm, received categories, genres, and generic expectations unfold and reformulate in ways that astonish and delight me. The volume is full of that most ancient of lyric genres, love poems — love found, lost and mourned — but the narrative thread is so subtle, the textual turns and linguistic swerves of the poetry so dazzling, that the “story” functions almost chorically. It tethers the soaring, dancing poetic voice like the kite’s string to the body’s hand. [ . . . ] We enter as well for the way lonsinger mindfully reflects on all that has touched her. [Also] characteristic is the conceptual brilliance of Whelm, beginning naturally enough with the connotations that “whelm” activates: meaning both M.E. overwhelm and O.E. helma to handle (O.N. hjalm, rudder). Whelm

– Cynthia Hogue recommends Whelm on Ron Slate’s on the Seawall

the nested object

The poems in dawn lonsinger’s chapbook the nested object inhabit a physical world. They wouldn’t be out of place beneath the sea, in a forest, some place plentiful with amorphous jellyfish or moss. Poem after poem is rooted in the organic; we watch sea urchins breed, peer into birds’ nests and cling to the roots of trees. This is elemental, more so than what usually passes for nature poetry. We are not in Wordsworth’s territory either, where each encounter with nature incites reflection and transcendence. Instead, “this is where shape incubates” (“the nested object”). Whitman or Thoreau would be more at home in these poems and both are, in fact, used as epigraph for “A Wreck of Nerves // & Birdlime,” and “And Thus the Darkness Bears,” for here the body—our bodies—are just as much a part of the natural world as fire, gourds, the moon. lonsinger is interested in the spaces between things, the wild element in each of us. In these poems, even a familiar children’s game is painted in a new light, so that it becomes beautiful and strange. [ . . . ] In a letter to autumn from the poem “is there anything left in the leaves to speak of” the final line accurately describes what any avid poetry lover seeks from a new encounter with the text: “For me, I only ask that my face, like the expression of trees, is blown apart a bit by the wind.” This book delivers on that request.

– Review by Valerie Wetlaufer at Poets’ Quarterly

The Linoleum Crop

winner of the 2007 Jeanne Duval Editions Chapbook Prize, chosen by Thomas Lux

“In dawn lonsinger’s beautiful, unsettling poems, the surface is a depth in itself—which is to say, there’s nothing superficial in her lovely troubling of language. She writes about ‘what is real, difficult in the sheen.’ Linoleum Crop looks to the spooky liminals: median strips, guardrails, windshields, as well as invisible boundaries. Her powerfully uncanny poems bear new and difficult witness to human and inhuman nature; they consider the assailable and unassailable, the glares of excess and evanescence: “So swam the surplus age, blindingly bright, away.” Linoleum Crop resists steady interpretations to gift us with all there is, a plurality of substance.”

— Alice Fulton

Still Life with Poem: Contemporary Natures Mortes in Verse

edited by Jehanne Dubrow & Lindsay Lusby, Literary House Press (2016)

“With a tradition that can be traced to Pompeii, the genre of the still life or nature morte has most often been used since the Middle Ages and the Renaissance as a vehicle for symbolism and metaphor, objects serving as stand-ins for philosophical ideas, religious principles, or moralizing messages. In Still Life with Poem, poets were asked to create (or to imagine) their own still lifes and to write poems in response to these thoughtful arrangements of things. And although still life paintings are often viewed as unmoving, quiet works of art, this anthology presents a collection of energetic, urgent voices; these poems speak to current events, the making of art, the domestic, the past, the body, faith, the environment, and the losses we all face.”

The Book of Scented Things: 100 Contemporary Poems about Perfume

edited by Jehanne Dubrow & Lindsay Lusby, Literary House Press (2014)

“What if 100 contemporary American poets were sent individually selected vials of perfume, each fragrance chosen to reflect the author’s voice, aesthetic, or writerly obsessions? What if they were asked to write new poems in response? The Book of Scented Things collects the results of this strange, aromatic experiment: poems of longing and of childhood memory, poems of place and philosophy and politics, poems about the challenge of writing poems about perfume. This is an anthology whose words will linger on your pulse points long after even the base notes have faded.”

Best New Poets 2010

edited by Claudia Emerson

“Best New Poets has established itself as a crucial venue for rising poets and a valuable resource for poetry lovers. The only publication of its kind, this annual anthology is made up exclusively of work by writers who have not yet published a full-length book. The poems included in this eclectic sampling represent the best from the many that have been nominated by the country’s top literary magazines and writing programs, as well as some two thousand additional poems submitted through an open online competition. The work of the fifty writers represented here provides the best perspective available on the continuing vitality of poetry.”

IOU: New Writing on Money

edited by Ron Slate

“A fascinating multi-genre book on the theme of money—good, bad, and otherwise. It includes work from Jonathan Ames, Augusten Burroughs, Mark Doty, Dolly Freed, Michael Greenberg, Tony Hoagland, Robert Pinsky, Jess Row, Mona Simpson, and 50+ writers, poets, and bank robbers. These diverse voices have a lot to say about money.”

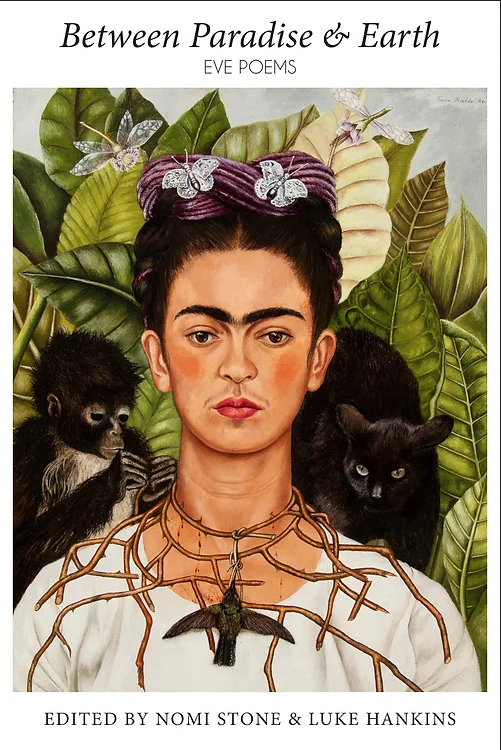

Between Paradise & Earth: Eve Poems

edited by Nomi Stone & Luke Hankins

“The recent and contemporary poems about the biblical figure Eve gathered in this anthology refuse given narratives. Here, poets of diverse backgrounds and traditions conjure a heterogeneous concert of Eves to reckon with desire, blame, power, gender, the body, race, politics, religion, knowledge, violence, and time. She becomes a door for dreaming of origins, for considering naming and language, for challenging assumptions and structures of power, and for examining the human condition. In these poems, Eve loves, grieves, rages, and proves a perennially relevant figure in our contemporary mythos.”

Contributors include Hala Alyan, Jericho Brown, Leila Chatti, Ama Codjoe, Rita Dove, Marie Howe, Ada Limón, Toni Morrison, and Ruben Quesada.